How an Atomic Bomb Destroyed a Girl's Life

An 89-year-old survivor relates her devastating encounter with the 1945 atomic bombing using pictures she has drawn.

Published

By Kaori Shitamichi, Eriko Noguchi and Teppei MatsumotoReporting from Hiroshima, Japan

Sadako Suemasa clearly remembers the morning of Aug. 6, 1945, when as an 11-year-old she witnessed the atomic bombing of the city of Hiroshima in western Japan.

“It was a cloudless, bright, blue-sky morning,” 89-year-old Suemasa began her story before an audience at an event in a neighboring city in February.

“I saw people covered in blood, with their skin hanging off, and countless dead bodies flowing in the river.”

That day, a U.S. B-29 bomber named the Enola Gay dropped an atomic bomb on Hiroshima, then home to 350,000 civilians and military personnel.

It was the first detonation of an atomic bomb in war. Three days later, the United States exploded another atomic bomb over Nagasaki.

Suemasa has conveyed her experience to younger generations for nearly 10 years using crayon pictures she has drawn. "I've liked drawing since childhood."

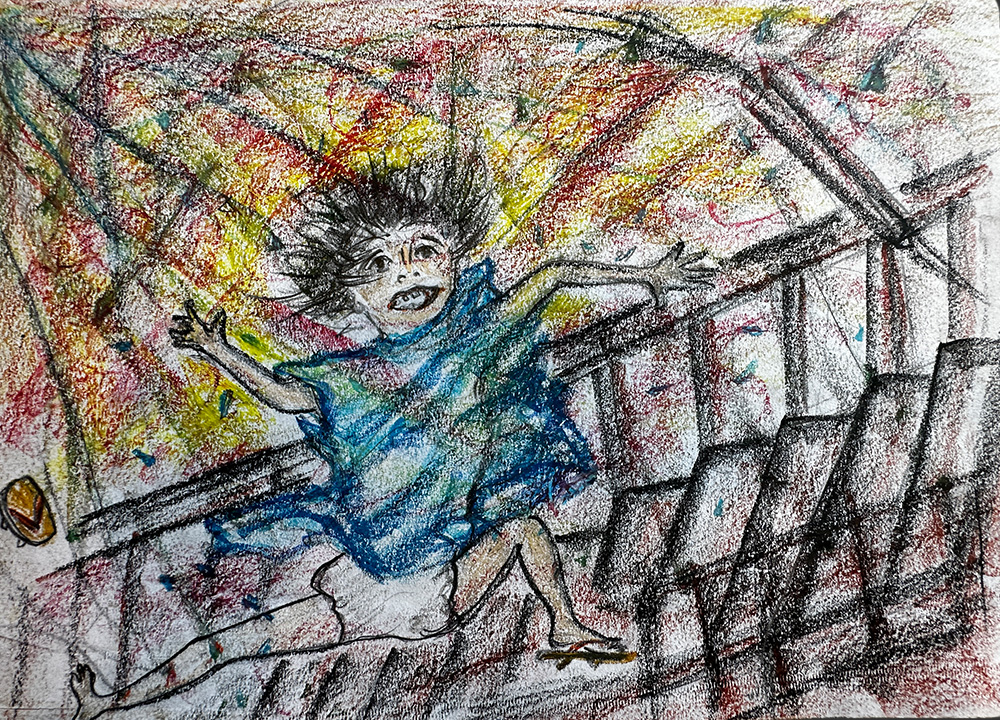

When the bomb exploded at 8:15 a.m., Suemasa was in a stationery shop near her elementary school. She wanted to buy a red crayon. Right after the shopkeeper told her he did not have one in stock, she saw a flash of light like a lightning bolt that was followed by a loud blast.

“Clouds of red dust were thrown up and broken glass was stuck in my head and legs,” she recalls.

She was also exposed to radiation, being just 2 kilometers away from the hypocenter.

I was only a sixth grader when the bomb hit.

I was near my elementary school, 2 km away from the epicenter.

Shards of broken glass hit my head and legs.

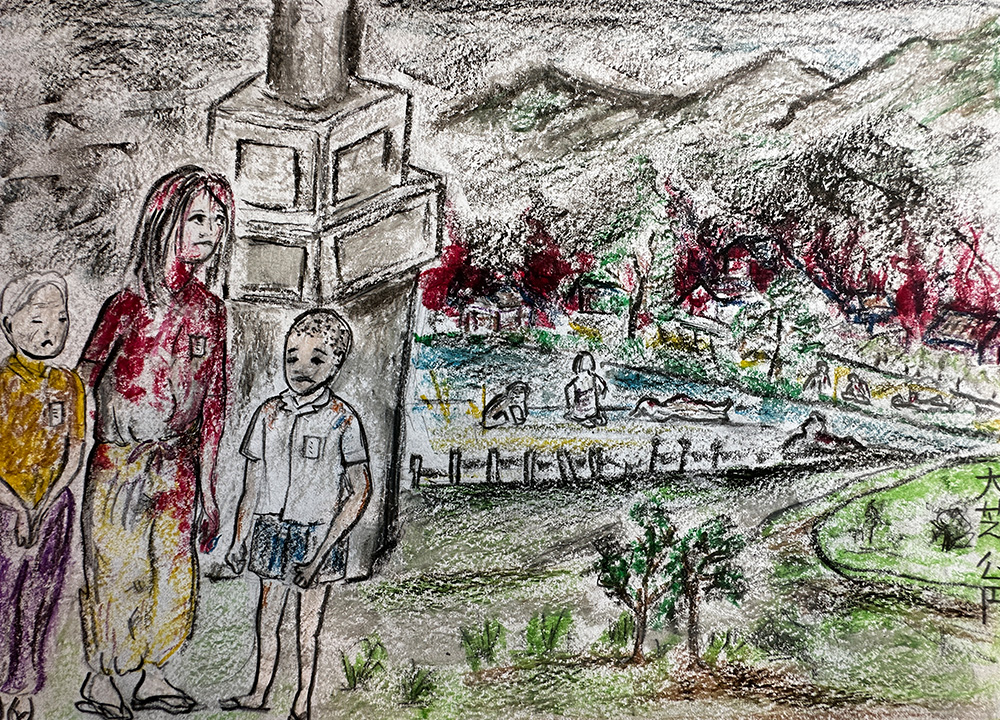

Suemasa lost her wooden sandals and fled frantically to a park where her family had decided to meet up if something bad happened. “Mommy, help me!” she cried out.

“Every house I saw on the way was on fire. I also saw a few of my friends lying on the ground. I called their names, but they didn't move at all. I soon found out they were dead.”

She finally arrived at the park and found her mother, younger brother and grandmother there. It took another few days for her to be reunited with other family members.

"When I saw my mother I ran toward her and hugged her, but she said it hurt."

Her mother, Tsuneyo, was badly burned by the extreme heat caused by the bomb and shards of glass were lodged all over her body.

“The skin of my mother's left wrist was hanging. She was like a ghost. It scared me a lot,” Suemasa recalls.

I heard a loud sound after a bluish-white flash of light. I thought the Earth was breaking up. In an instant, many people were pushed to the depths of hell, made worse by pain, and burned to death like a bug.

I tried to hold on to something, but the blast blew me a few meters. The next moment I found myself in the middle of a staircase in the stationery shop and fell down a few steps.

I decided to go to a park where my family was to meet up in case something bad happened. I couldn't run well because my legs were injured. As I went past my elementary school, I saw four or five friends of mine lying on the ground. I called their names, but they didn't respond.

When I finally arrived at the park, my mother, younger brother and grandmother were already there. My mother was bleeding because of broken glass and her skin was hanging down due to serious burns. My mother shouted, "Sadako, you are alive!"

The Magnitude of A-Bombs

As Japan pursued its military goals, Hiroshima developed and served as a crucial troop dispatch base from the 1894-1895 First Sino-Japanese War. Its location and well-developed railway networks were convenient for deploying troops and sending supplies to battlefields in Asia.

Toward the end of the Pacific War that followed Japan's surprise attack on Pearl Harbor in Hawaii in 1941, the United States identified Hiroshima and Nagasaki, another city key to Japan's war efforts with many munitions factories, as targets for nuclear weapons as it sought to end the yearslong war.

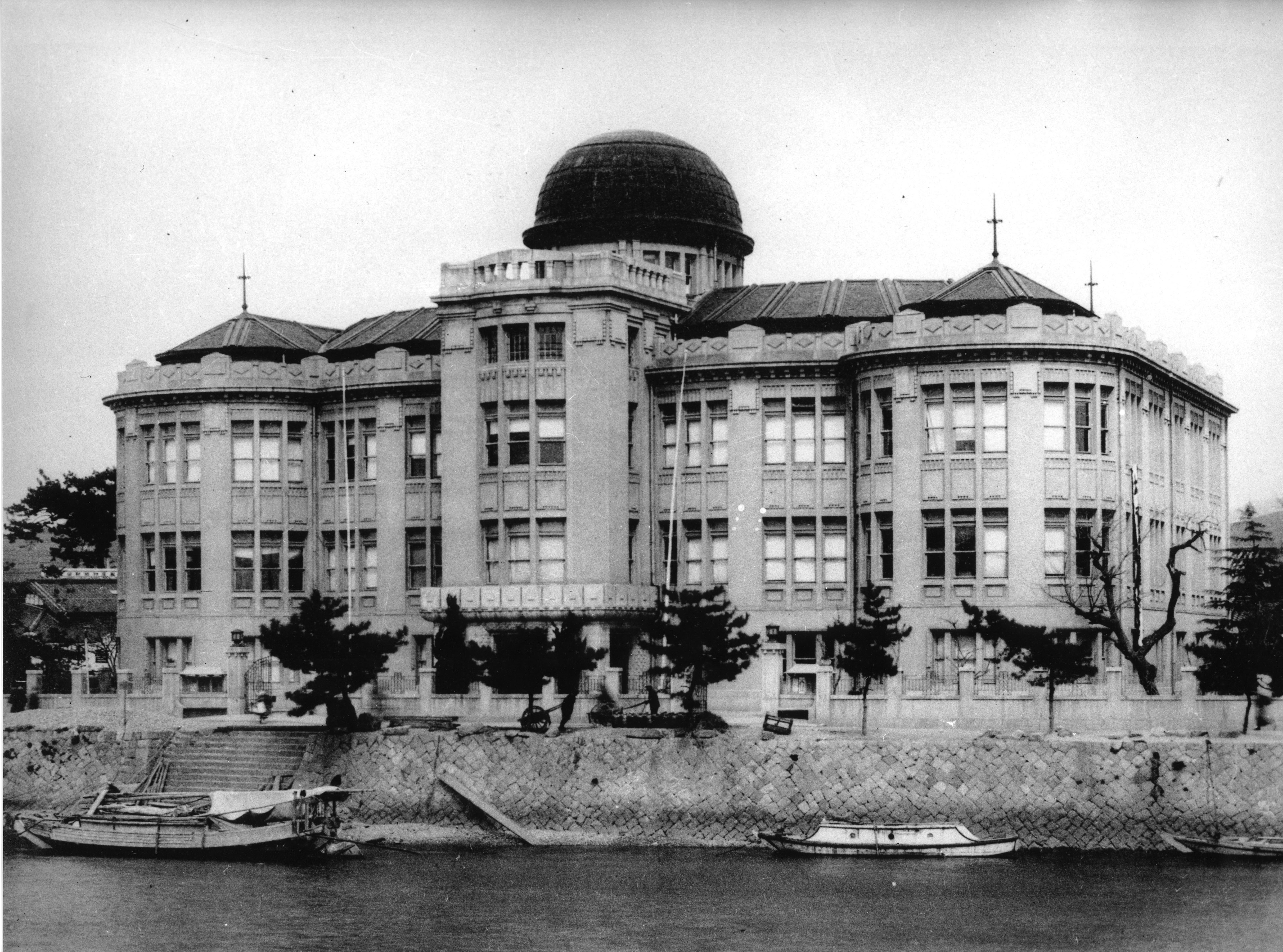

The uranium bomb dropped on Hiroshima exploded 600 meters (1,970 feet) above a crowded area where a cinema, shops, cafes and schools were located, including a Neo-Baroque-style building now known as the Atomic Bomb Dome that stands as a symbol of the devastation.

Near ground zero, people were severely burned and the bomb blast slammed them into nearby buildings, causing instant death.

Those who were some distance away still suffered serious burns. Others were trapped in collapsed houses or caught in fires following the blast.

The Two Bombs Dropped on Japanese Cities

| Hiroshima | Location | Nagasaki |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

| Aug. 6, 1945 | Date | Aug. 9, 1945 |

| Uranium | Type | Plutonium |

| 16 kilotons | Total energy | 21 kilotons |

| 350,000 | Estimated population | 240,000 |

| 140,000 (±10,000) |

Estimated deaths by the end of 1945 |

74,000 |

| 51,787 | Buildings completely destroyed or burned |

12,900 |

Although the exact number of deaths caused by the atomic bombs remains unclear, the Hiroshima city government estimates roughly 140,000 people had died by the end of 1945, some due to insufficient medical treatment, with 74,000 deaths estimated in Nagasaki.

Of the victims in Hiroshima, nearly half who were within 1.2 km (0.75 miles) of the hypocenter are believed to have died that day. Within a 2 km radius of ground zero, raging flames burned down almost all of the buildings.

.png)

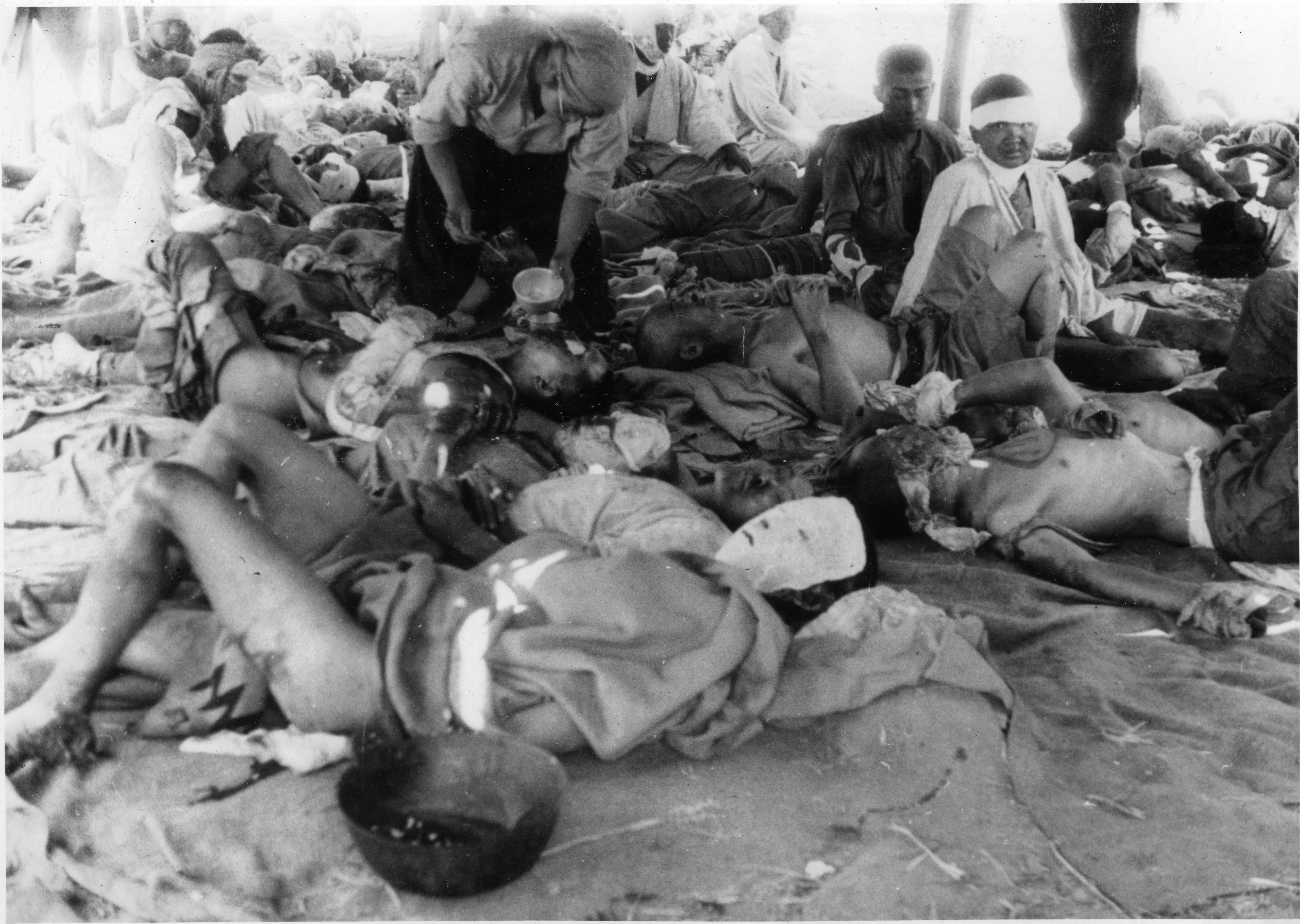

People suffered from radiation-induced symptoms, too.

Within two weeks of the explosions, many people in Hiroshima and Nagasaki developed acute symptoms such as fever and vomiting.

Day 1 - (approximately)Day 14

External Injuries

Symptoms Induced by Radiation

Top: People at a makeshift first aid station in Hiroshima in a photo taken by Yotsugi Kawahara. (Photo courtesy of Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum)

Left: Central Hiroshima photographed by the U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey. (Photos courtesy of Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum)

Right: Central Hiroshima photographed by the U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey. (Photos courtesy of Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum)

After around two weeks, symptoms such as hair loss and internal bleeding were reported.

People who entered the city after the bombing to search for family members, relief workers as well as those exposed to radioactive "black rain" developed symptoms similar to those of people directly exposed to radiation.

By October 1945

Symptoms Induced by Radiation

As acute symptoms subsided by around the end of 1945, many people believed the health effects of the atomic bombing were over. But they were not.

A medical survey reported that diagnoses of leukemia peaked several years after the bombing. Increasing cases of lung, breast and thyroid cancer were reported as time passed.

By the end of 1945

External Injuries

Symptoms Induced by Radiation

Some children exposed to radiation while in the womb were born with physical and intellectual disabilities. Their brains were half as small as those of other children at the same age.

Atomic bomb-induced diseases continue to afflict survivors today. Scars and rumors that the effects of radiation were infectious led to discrimination against survivors. Some suffered post-traumatic stress disorder and psychological distress due to the loss of their family members.

Months later - Present

External, Social and Psychological Injuries

Symptoms Induced by Radiation

Pains Like No Other

For Suemasa, Aug. 6, 1945, was the day she lost her childhood, she said.

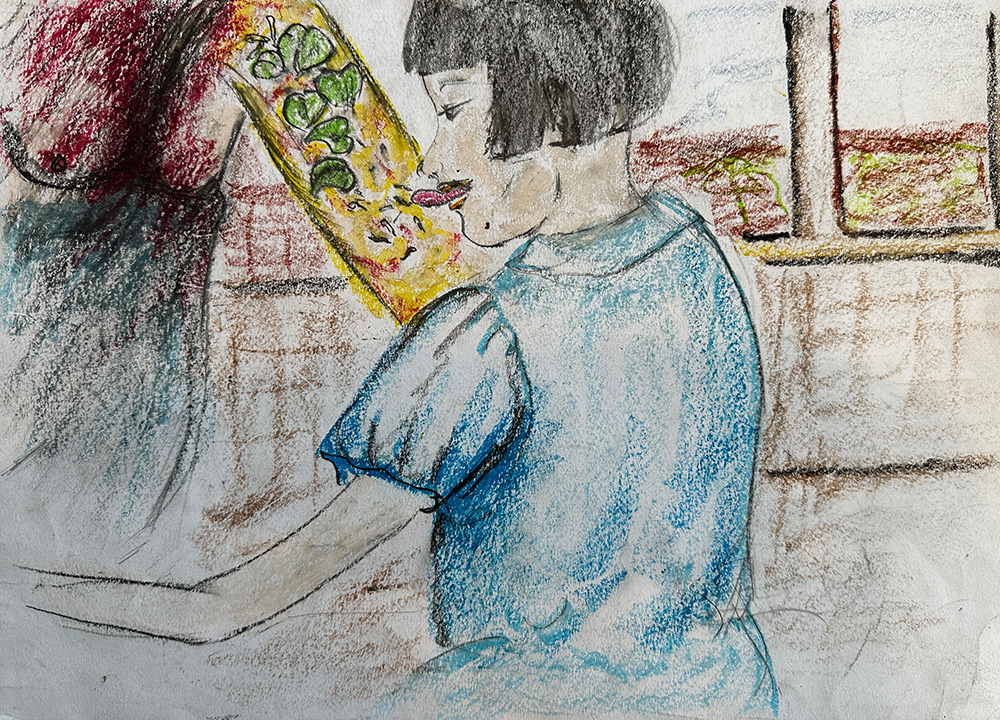

"My relationship with my mother was reversed after that day. My mother would cry like a child, saying, "It hurts, Sadako. It hurts." Seeing her suffer, I thought I couldn't be a child any longer."

She began to look after her suffering mother.

"I only wanted to remove all the pain my mother was suffering. I believed that was my role."

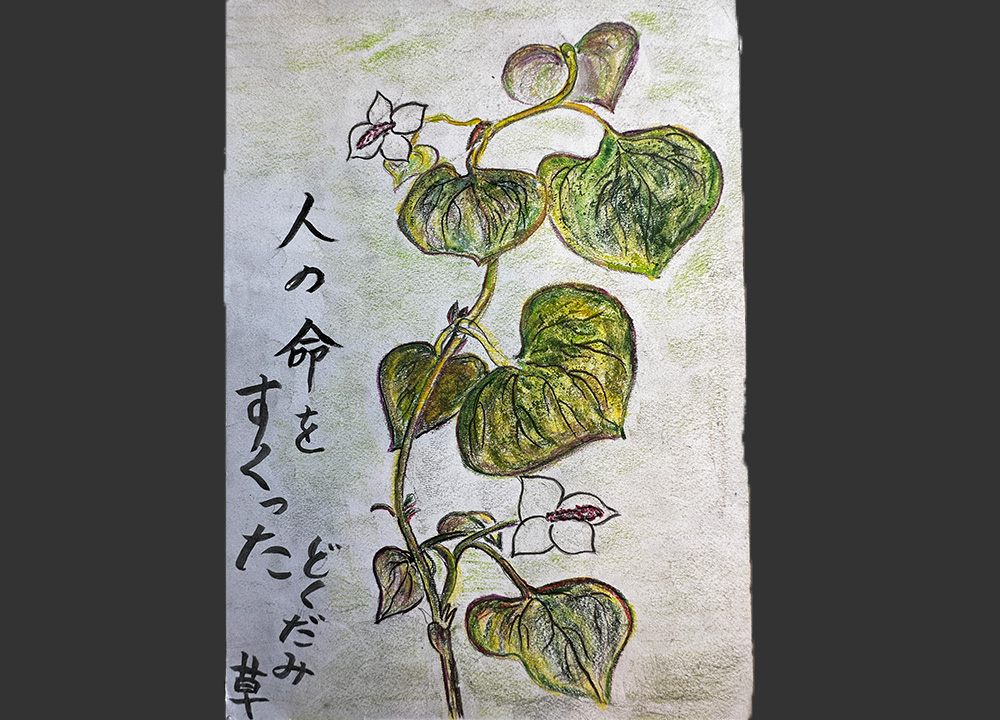

She soothed her mother's burns with wet "dokudami" herbs and even used her tongue to remove maggots from her mother's wounds in order to minimize the pain.

"My mother said it hurt when I removed them with my fingers. So I did it that way. You might find it weird, but I didn't care because she was my only mother."

One day, she made her mother drink human bone powder she brought back from a makeshift cremation site, after hearing a rumor that it would be effective for burn patients.

“Though I just wanted to relieve her pain, I feel sorry for doing that sort of thing to her.”

The first thing I did was allow my mother some rest, then I would wet the leaves of dokudami herbs with my saliva. After kneading the leaves with my hand, I would put them on my mother's burned left wrist.

When the herbs got dry from body heat, they would fall away with yellow pus. As the pain eased, her face seemed to relax. I changed the herbs every two hours.

Before long, maggots infested my mother's wrist. I removed them with my tongue as doing it with my fingers hurt her. I didn't hesitate because I loved my mother. I was like a little nurse.

My mother would say, "Thank you, Sadako. Thank you." "You're alright. You'll get soon better," I would tell her as if I were her mother.

Mother's Death

Suemasa's mother died of lung cancer in 1956, after years of skin soreness and fatigue. Her younger brother died of liver cancer in 1991 when he was 54 years old.

She has no doubts that their deaths were caused by exposure to radiation. "This is how people die from an atomic bomb."

Suemasa herself suffered from liver disease and was hospitalized for six months at the age of 27 after she got married and gave birth to two boys.

It was not until she was an adult that the remaining shards of glass in her body were finally removed.

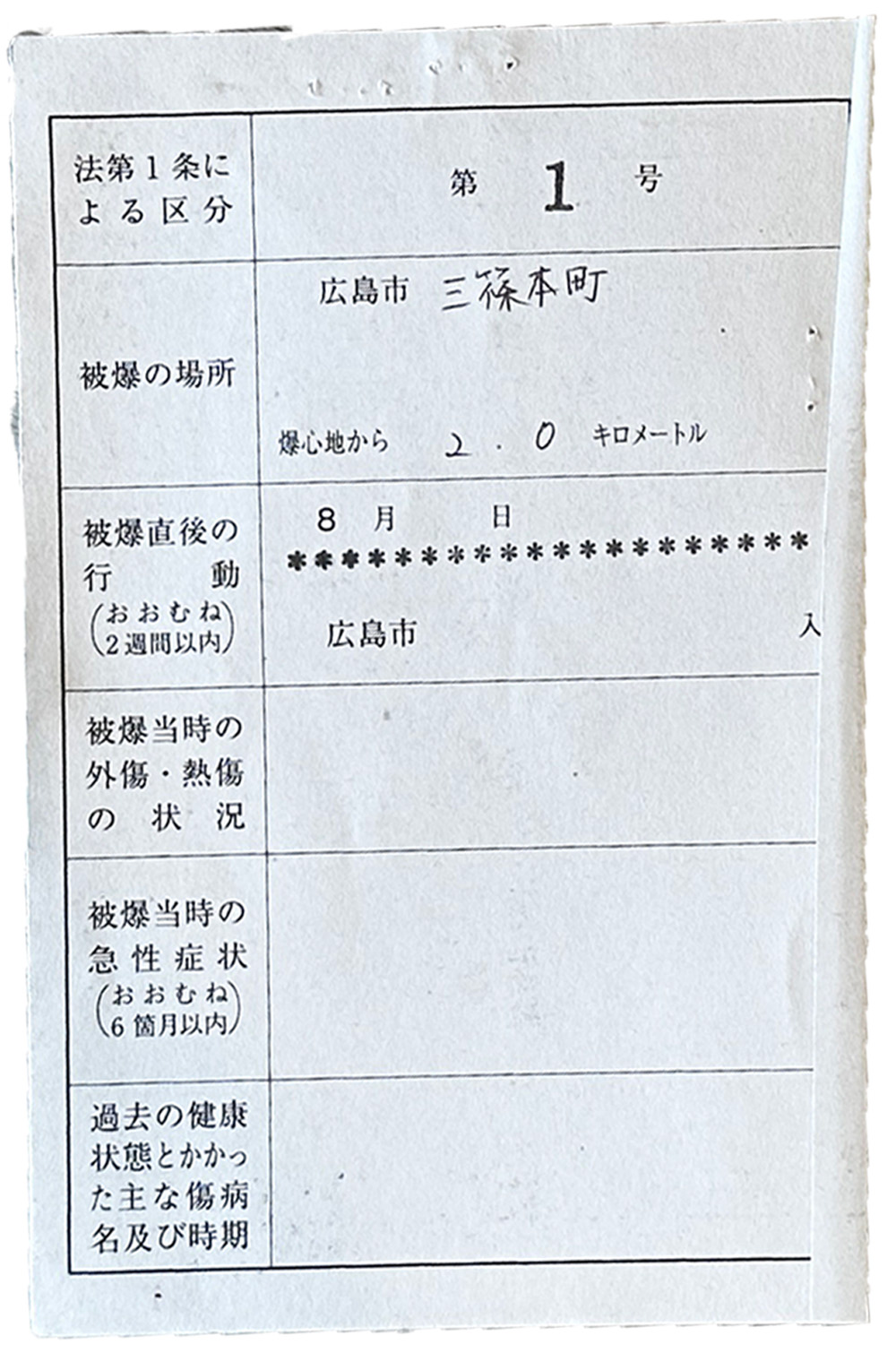

Left: Suemasa's atomic bomb survivor's certificate issued by the city government, which mentions she was exposed to radiation within 2 km of the hypocenter. Designated survivors are not charged for medical treatment. (Kyodo)

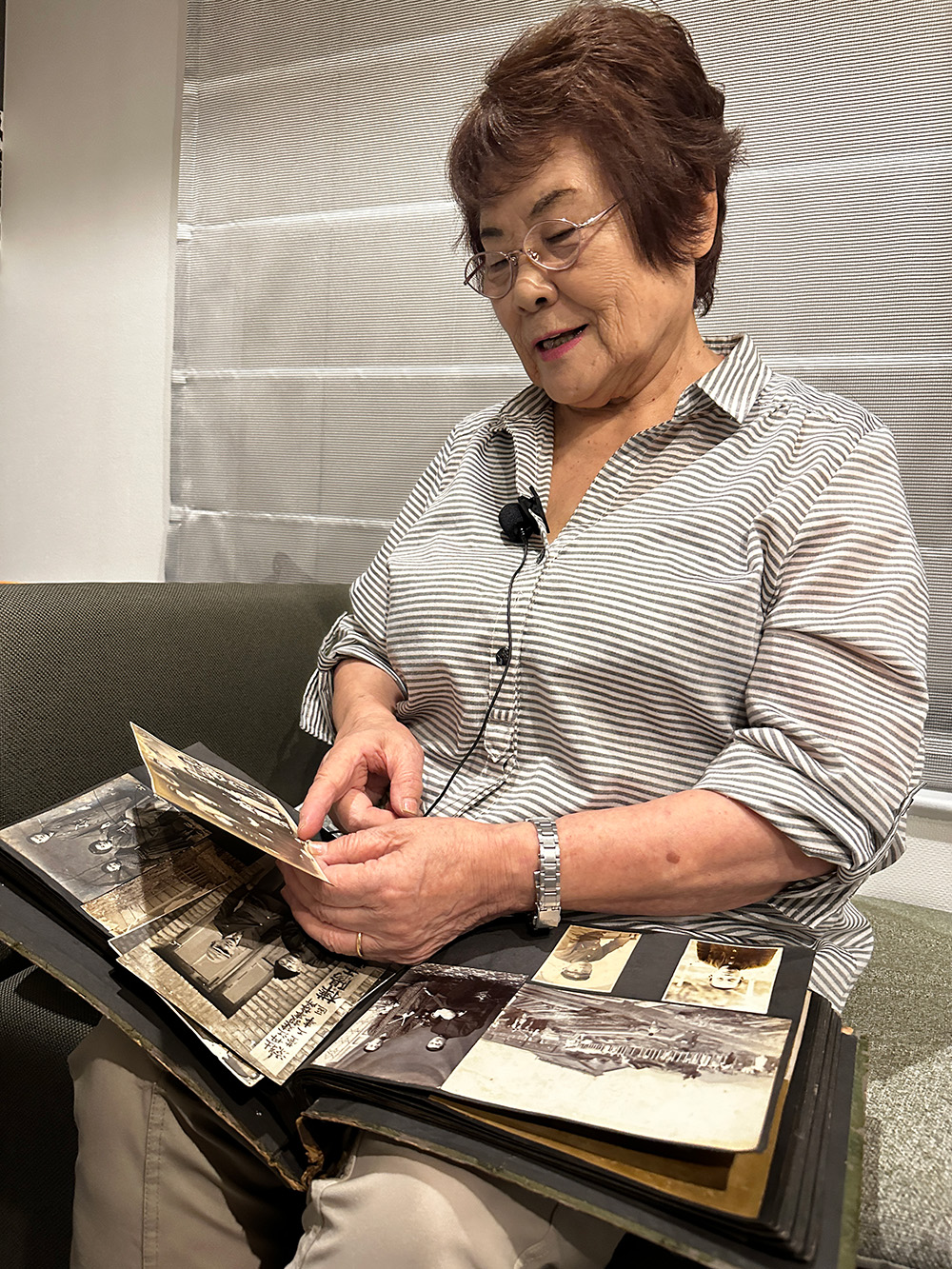

Right: Suemasa holds her family album on July 21, 2023. (Kyodo)

top: Suemasa's atomic bomb survivor's certificate issued by the city government, which mentions she was exposed to radiation within 2 km of the hypocenter. Designated survivors are not charged for medical treatment. (Kyodo)

Bottom: Suemasa holds her family album on July 21, 2023. (Kyodo)

While the city was quickly rebuilt after the war, it took a long time for Suemasa to start sharing her traumatic experience before audiences. She had even been reluctant to attend the city's commemorative ceremonies held every Aug. 6.

But she now believes that passing on her stories to young people serves a significant purpose.

"I don't want wars anymore. I don't want young people to experience the same horrible thing that I did. Living in peace is the best for humanity. I will tell people of my experience as long as I live."

The leaders of the Group of Seven major economies, including Japan and the United States, issued a joint statement in May called the Hiroshima Vision on Nuclear Disarmament, in which they said that "the overall decline in global nuclear arsenals achieved since the end of the Cold War must continue and not be reversed."

12,520

The estimated number of warheads

including retired warheads

But the reality is that the world is not moving toward the elimination of nuclear weapons. As of June, the number of warheads, including retired warheads, totaled 12,520, according to an estimate by Nagasaki University's Research Center for Nuclear Weapons Abolition.

The center has warned that a nuclear arms race is under way after the United States and Russia announced in 2018 that they had achieved the goal of restricting the number of warheads as agreed under the New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty, or New START.

And Japan, which remains the only country to have suffered nuclear attacks, has categorically refused to join the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons on the grounds that the nuclear deterrence underpinned by the U.S. nuclear umbrella is crucial to safeguarding the country.

Suemasa says world leaders need to feel and come to know the real suffering of the hibakusha, or atomic bomb survivors.

"No one has the right to kill people."

Text and Web design by Teppei Matsumoto

Photos courtesy of Sadako Suemasa unless otherwise indicated

Pictograph design by Miyuki Nakaji and Motoki Akamine

Editing by Daisuke Yamamoto and Riz Ahmad